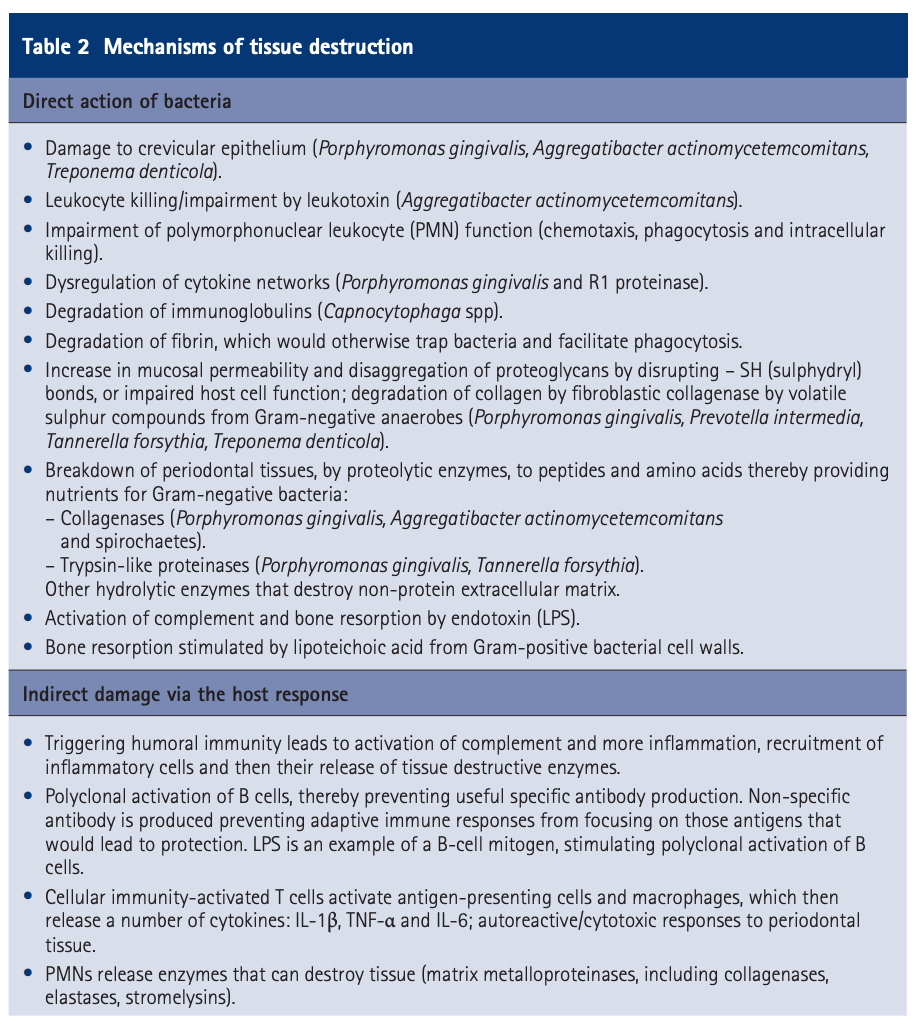

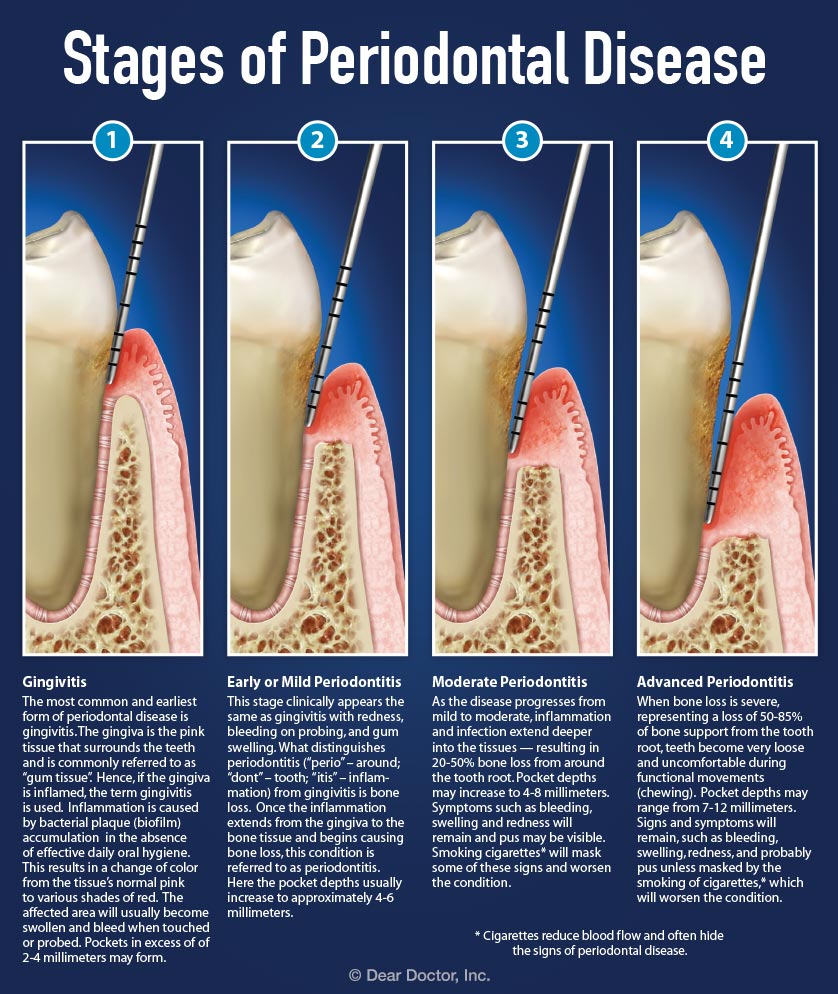

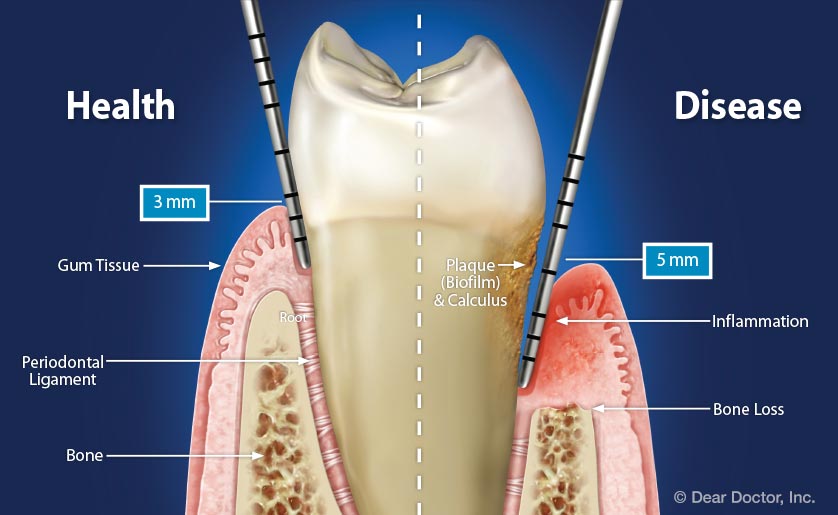

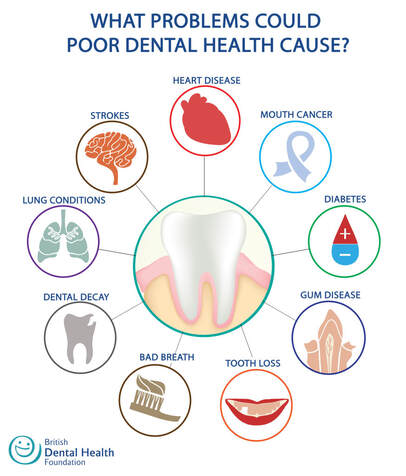

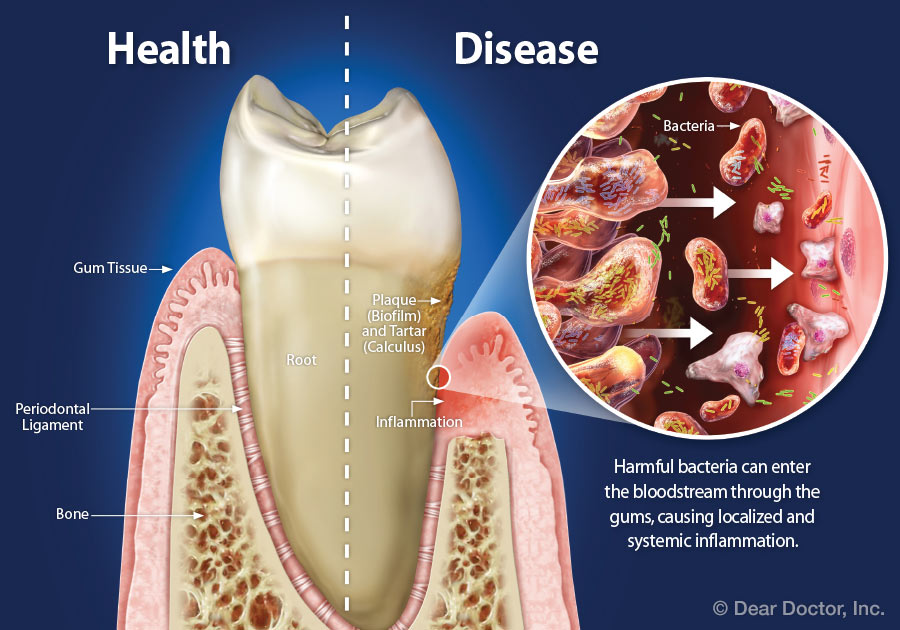

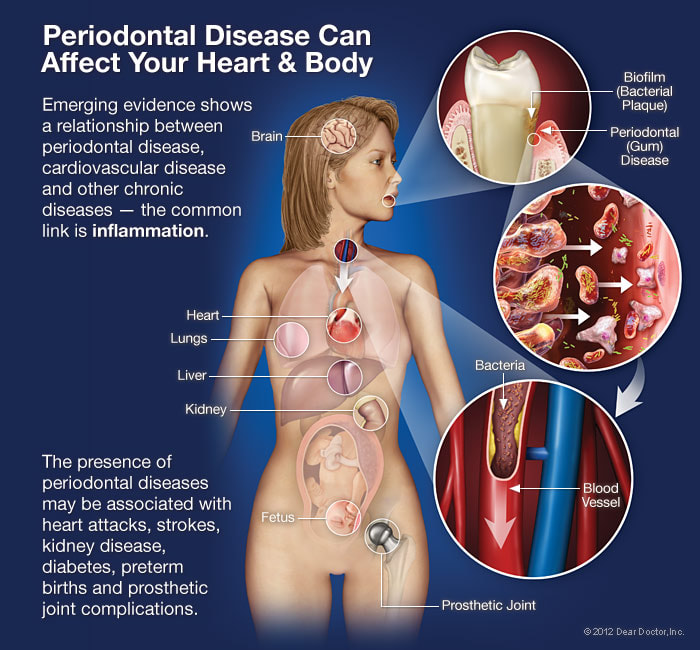

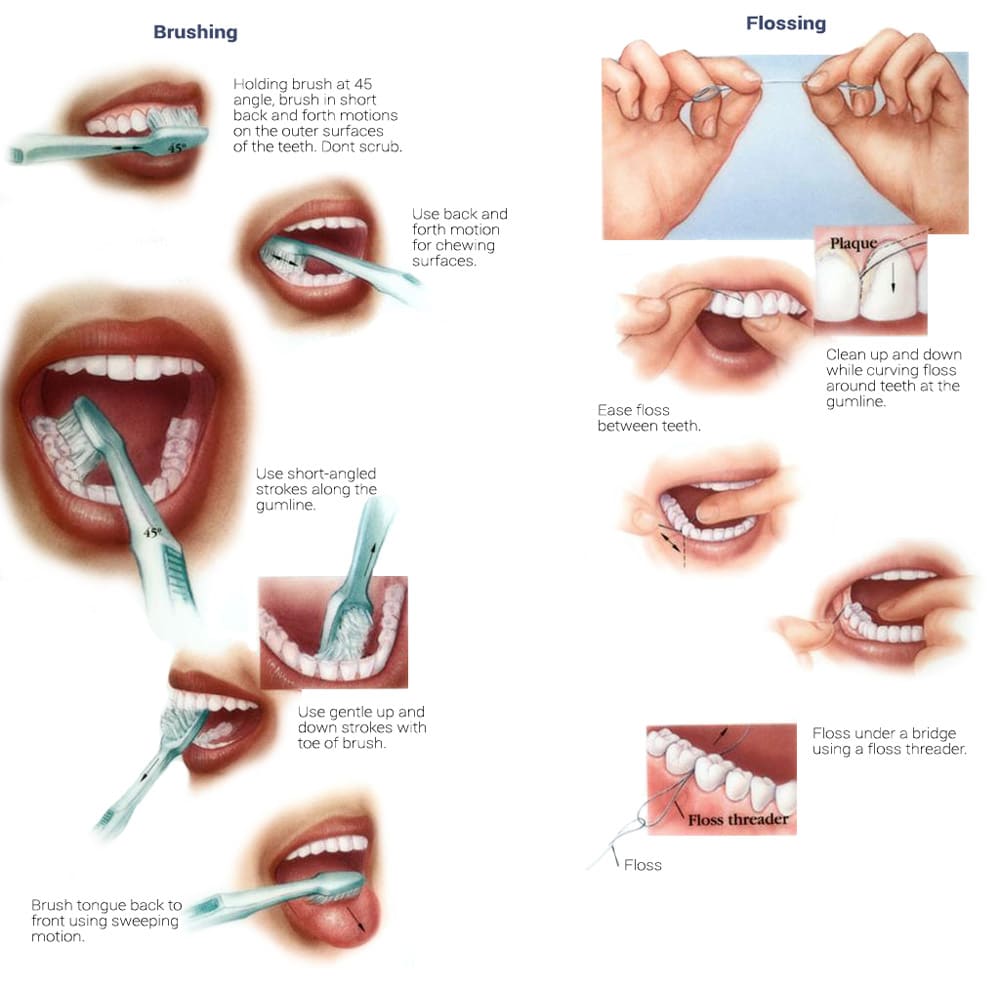

Overview The phrase “long in the tooth” was originally used as a reference to a horses age, as unlike human teeth, their teeth continue to grow with age. As we get older, we may begin to notice that our teeth begin to look longer, however this is not due to the teeth themselves growing in length but due to gingival recession. While some attachment loss is “normal,” the loss in gum tissue makes it appear as if our teeth are longer by beginning to expose the roots of our teeth which can not only be aesthetically displeasing but also indicative of periodontal disease. It is preventable and important to catch it early, stop its progress, and prevent it from continuing. Periodontal disease can begin as an acute condition and progress to a chronic ailment. There are a number of factors that influence the development and progression of periodontal disease. These include smoking, diabetes, poor oral hygiene, stress, genetics, crooked teeth, underlying immune-deficiencies such as AIDS, fillings that are defective, medications that cause dry mouth, ill-fitting prosthetics, and female hormonal changes such as with pregnancy or use of oral contraceptives. Periodontal disease results from infections and inflammation of the gums and bone that surround and support the teeth caused by the presence of bacteria. It is sometimes commonly known as gingivitis which refers to the early stages of the disease which can progress to a serious condition called periodontitis, resulting in gingival recession where the gums pull away from the tooth, bone loss occurs, and teeth begin to loosen and fall out. According to the CDC, 47.2% of adults aged 30 years and older have some form of periodontal disease. Periodontal disease increases with age, with 70.1% of adults 65 years and older having periodontal disease. This condition is more common in men than women (56.4% vs 38.4%), those living below the federal poverty level (65.4%), those with less than a high school education (66.9%), and current smokers (64.2%). The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey for 2009-2010 found that more than 47% of American adults have been diagnosed with periodontitis (Wu et al., 2015). Etiology/PathogenesisWith over 600 species of bacteria that can be found in the periodontal pocket, it is difficult to determine the specific organism responsible for periodontal disease. A key difference between the bacteria that cause decay on the smooth surfaces of the anatomical crown of the tooth are aerobic, as opposed to the anaerobic bacteria that thrive in deep tissues such as periodontal pockets where the oxygen supply is limited. These bacteria release exotoxins that irritate the gingival tissue initiating an inflammatory response which can be detrimental to the healthy surrounding tissues if allowed to progress. Some pathogens identified for periodontal disease Treponema denticola and Porphyromonas gingivalis, but cannot ultimately be declared the only responsible bacteria. Pathology/ Mechanisms of DiseaseBiofilm in the oral cavity attracts bacteria to adhere and grow, limiting the diffusion of nutrients and oxygen which ultimately contributes to an anaerobic environment in which the bacteria that are responsible for periodontal disease thrive. Gingivitis/periodontitis is considered to be a chronic inflammatory lesion that both, our innate and adaptive, immune responses work together to manage the infection. It is the toxic byproducts of the bacteria that trigger the epithelial cells of the gingiva to produce cytokines to indicate the need for an immune response, dilating the blood vessels in the process which is why the gums begin to turn red from their normal pink shade and bleed easily when brushing or upon probing during periodontal charting procedures. The toxic byproducts also affect oseoclastogenesis via RANKL, interleukin-1beta, interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor alpha and prostaglandin E2 (Cekici et al., 2014). Clinical ManifestationsWhen visiting the dentist, patients are often times asked if they ever see any bleeding when they brush their teeth, which is the primary indicator that harmful bacteria are present in the periodontal pocket. Healthy gums should be a pale pink color and tight, as opposed to red and swollen which results from the inflammatory response of our bodies. The gums may feel tender and bleed with even the gentlest touch which is consistent with the vascular response and increased permeability of the blood vessels. Other symptoms include bad breath, or a bad taste that won’t go away, clinical attachment loss of the gum tissue and exposed roots of the teeth, sensitivity to temperature, and increased mobility in teeth. Severe and chronic periodontal disease can cause destruction of bone and therefore those with oral prosthetics such as partial or full dentures may begin to notice a change in how they fit. This change is evident upon radiographic assessments which can be used to monitor the pattern and extent of alveolar bone loss. DiagnosisThere are a number of terms used when referring to periodontal disease such as gingivitis or periodontitis. These various terms are used to stage the progress of the disease defined by the breakdown of hemidesmosomes and resorption of alveolar bone. The depths of the groove around each tooth between the gums and teeth is measured at six sites during a periodontal assessment. This charting can help monitor changes in attachment and bone loss. The World Health Organization has maintained a community periodontal index (CPI), scoring the stages of periodontal disease (Preshaw, 2015). Bleeding upon probing is noted during periodontal probing. A radiological assessment can also be done to compare relative bone levels over time to determine whether the condition has progressed or is in an arrested state. Additional information that may be collected is the amount of gum recession/loss of attachment, tooth mobility, and involvement of the tooth furcation, the area under teeth with multiple roots such as the molars where two of the roots join the crown of the tooth. InputsSmoking can have detrimental consequences all over the body, understandably including the oral cavity, where smoke such as from tobacco products can contain a number of harmful chemicals, many of which are known carcinogens (Zee, 2009). One such chemical is carbon monoxide, which decreases the availability of oxygen in the blood that perfuses the gum tissue. This provides the perfect environment for the opportunistic anaerobic bacteria that cause periodontal disease. The primary mechanism in which smoking contributes to periodontal disease is the effects of nicotine on how effective the inflammatory response, impairing the body's ability to fight off infection. A study showed a significant decrease of immunoglobulins such as IgA and IgG in smokers versus nonsmokers. Nicotine also acts as a vasoconstrictor which decreases oxygen supply to the tissues which can result in delayed wound healing (Silva, 2021). Systems IntegrationDiabetesPeriodontal disease and diabetes have a bidirectional relationship. Diabetes increases osteoclast activities via oxidative stress in areas of inflammation, such as that of the gingiva, which potentiates the amount of bone resorption seen, increasing the depth of the periodontal pocket (Wu et al., 2015). The persistence of a low grade chronic infection leads to a build- up of reactive oxygen species which can cause diabetic complications such as stroke, neuropathy, retinopathy, and nephropathy (Asmat et al., 2016). Cardiovascular DiseaseA complication of periodontal disease is the ability for oral bacterial species, such as P. gingivalis, to enter the circulatory system which can cause bacteremia. Studies done on animal models have shown a correlation of the presence of oral pathogens to not only increased alveolar bone loss but also to increased aortic atherosclerosis, confirmed by testing the DNA of atheromatous plaques (Bui et al., 2018). Because periodontal disease is considered to be a chronic infection, the continued production of liposaccharides and inflammatory cytokines may contribute to the pathogenensis of athersclerosis and thromboembolic events (Dhadse et al., 2010). Self-Check QuestionTrue or False: Is our immune response to bacterial pathogens partially responsible for the progression of periodontal disease and the destruction that results in alveolar bone loss? ExtrasOral Hygiene ReviewPrevention is key! Establishing a dental routine early on and perfecting your brushing technique will help you keep your teeth clean and minimize dental work (and bills)! This should not only include a biannual (q 6 month) dental cleaning/ examination + radiographs to catch things early before they turn into bigger problems, but to also put in the effort at home, whether you brush twice a day or after each meal + flossing and with the aid of the Waterpik, a tool especially helpful for those with dental implants. WaterpikBrushing alone is not enough. In addition to flossing, using a waterflosser such as Waterpik's Cordless Advanced will help keep your teeth and the areas below the gum line free of debris. Contrary to its name, a "waterflosser" is not synonymous with traditional floss. While floss works well cleaning the areas between the teeth, a waterflosser acts as a "power washer" which flushes the area around your tooth below the gumline, a place where the bristles of your toothbrush and floss cannot reach. (YouTube, 2018) While the Waterpik is considered a water "flosser," it is not interchangeable with traditional flossing. Each tool works on different areas. The brush cleans the smooth surfaces of the teeth, floss works in between the teeth and the Waterpik flushes out the gutter around the tooth. Gingival GraftingSometimes, periodontal disease progresses to a point where irreversible damage has been done which can leave you feeling subconscious about your smile. Luckily, there's a solution to gum recession with periodontal mucosal grafting. Tissue is removed from the palate of the mouth and grafted over the exposed root of the tooth with esthetically pleasing results. ReferencesAlexandridi, F., Tsantila, S., & Pepelassi, E. (2018). Smoking cessation and response to periodontal treatment. Australian dental journal, 63(2), 140–149. https://doi.org/10.1111/adj.12568

Alvarez, C., Monasterio, G., Cavalla, F., Córdova, L. A., Hernández, M., Heymann, D., Garlet, G. P., Sorsa, T., Pärnänen, P., Lee, H. M., Golub, L. M., Vernal, R., & Kantarci, A. (2019). Osteoimmunology of Oral and Maxillofacial Diseases: Translational Applications Based on Biological Mechanisms. Frontiers in immunology, 10, 1664. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.01664 Asmat, U., Abad, K., & Ismail, K. (2016). Diabetes mellitus and oxidative stress-A concise review. Saudi pharmaceutical journal : SPJ : the official publication of the Saudi Pharmaceutical Society, 24(5), 547–553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2015.03.013 Bui, F. Q., Almeida-da-Silva, C., Huynh, B., Trinh, A., Liu, J., Woodward, J., Asadi, H., & Ojcius, D. M. (2019). Association between periodontal pathogens and systemic disease. Biomedical journal, 42(1), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bj.2018.12.001 Cekici, A., Kantarci, A., Hasturk, H., & Van Dyke, T. E. (2014). Inflammatory and immune pathways in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. Periodontology 2000, 64(1), 57–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/prd.12002 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013, July 10). Periodontal Disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/conditions/periodontal-disease.html. Chang, C. H., Han, M. L., Teng, N. C., Lee, C. Y., Huang, W. T., Lin, C. T., & Huang, Y. K. (2018). Cigarette Smoking Aggravates the Activity of Periodontal Disease by Disrupting Redox Homeostasis- An Observational Study. Scientific reports, 8(1), 11055. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-29163-6 Dhadse, P., Gattani, D., & Mishra, R. (2010). The link between periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease: How far we have come in last two decades ?. Journal of Indian Society of Periodontology, 14(3), 148–154. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-124X.75908 Fiorillo, L., Cervino, G., Laino, L., D'Amico, C., Mauceri, R., Tozum, T. F., Gaeta, M., & Cicciù, M. (2019). Porphyromonas gingivalis, Periodontal and Systemic Implications: A Systematic Review. Dentistry journal, 7(4), 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj7040114 Hasan, A., & Palmer, R. M. (2014). A clinical guide to periodontology: pathology of periodontal disease. British dental journal, 216(8), 457–461. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.299 Liccardo, D., Cannavo, A., Spagnuolo, G., Ferrara, N., Cittadini, A., Rengo, C., & Rengo, G. (2019). Periodontal Disease: A Risk Factor for Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease. International journal of molecular sciences, 20(6), 1414. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20061414 Loos, B. G., & Van Dyke, T. E. (2020). The role of inflammation and genetics in periodontal disease. Periodontology 2000, 83(1), 26–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/prd.12297 Lyle D. M. (2012). Relevance of the water flosser: 50 years of data. Compendium of continuing education in dentistry (Jamesburg, N.J. : 1995), 33(4), 278–282. Parisi, M. (2010). Can't Brush Teeth Alone. Off the Mark. Andrews McMeel Syndication. https:/www.offthemark.com/cartoon/careers-jobs/dentists/2010-07-26. Preshaw P. M. (2015). Detection and diagnosis of periodontal conditions amenable to prevention. BMC oral health, 15 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), S5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6831-15-S1-S5 Sanz, M., Marco Del Castillo, A., Jepsen, S., Gonzalez-Juanatey, J. R., D'Aiuto, F., Bouchard, P., Chapple, I., Dietrich, T., Gotsman, I., Graziani, F., Herrera, D., Loos, B., Madianos, P., Michel, J. B., Perel, P., Pieske, B., Shapira, L., Shechter, M., Tonetti, M., Vlachopoulos, C., … Wimmer, G. (2020). Periodontitis and cardiovascular diseases: Consensus report. Journal of clinical periodontology, 47(3), 268–288. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.13189 Silva H. (2021). Tobacco Use and Periodontal Disease-The Role of Microvascular Dysfunction. Biology, 10(5), 441. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology10050441 Stanko, P., & Izakovicova Holla, L. (2014). Bidirectional association between diabetes mellitus and inflammatory periodontal disease. A review. Biomedical papers of the Medical Faculty of the University Palacky, Olomouc, Czechoslovakia, 158(1), 35–38. https://doi.org/10.5507/bp.2014.005 World Health Organization. (n.d.). Oral health. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/oral-health. Wu, Y. Y., Xiao, E., & Graves, D. T. (2015). Diabetes mellitus related bone metabolism and periodontal disease. International journal of oral science, 7(2), 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijos.2015.2 YouTube. (2018). How to Use a Waterpik® Water Flosser. YouTube. How to Use a Waterpik® Water Flosser. Zee K. Y. (2009). Smoking and periodontal disease. Australian dental journal, 54 Suppl 1, S44–S50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1834-7819.2009.01142.x

0 Comments

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed